Interpretation & Awareness

The Bermuda National Trust is a 2021-22 participant in Re-imagining International Sites of Enslavement (RISE), a knowledge-sharing

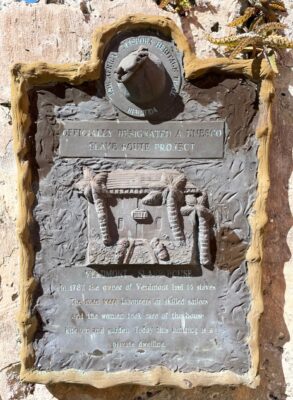

African Diaspora Heritage Trail Inscription at Verdmont

programme that brings together managers of sites around the Atlantic with a connection to the slave trade. The programme is a collaboration between International National Trusts Organisation (INTO) and the American National Trust for Historic Preservation. Practitioners working at INTO member sites are invited to share their experience of interpreting the history of slavery with their peers, with the support of Elon Cook-Lee, Director of Interpretation and Education at the NTHP.’

The RISE programme will strengthen the Trust’s reinterpretion of the many sites under our care and curation associated with the enslavement of people of African descent and related histories of Black resistance and empowerment. We recognise the need to carefully reflect upon, and expand in collaboration with the community, both the stories we tell and the ways we tell them. RISE will help us to do this in ways aligned with the forefront of heritage research and practice. We invite community members who would like to learn more about our participation in RISE and the evolving interpretative plan for the Trust’s museums, wider historic sites, collections and other heritage related to enslavement to contact Head of Cultural Heritage Dr. Charlotte Andrews.

Steps to possible quarters of enslaved people at Verdmont

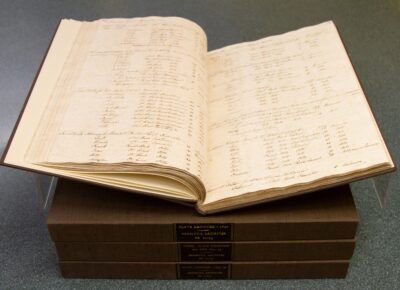

Below are links to searchable spreadsheets transcribing the Bermuda Slave Registers for 1821, 1827, 1830, and 1833-4. The original hand-written ledgers are held by the Bermuda Archives, which ‘collects, protects, and makes available, records of the Bermuda Government and private collections which have enduring historical and cultural value’.

Following the Slave Trade Act 1807, Slave Registers for British Colonial Dependencies were kept between 1813 and 1834, primarily to distinguish enslaved people who had been so-called ‘lawfully enslaved’ from those who were illegally trafficked from Africa to the British colonies. The Registers were usually revised every three years up until the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 led to the Emancipation of all enslaved people in the British Empire—including Bermuda—from 1 August 1834.

Dr. Virginia Bernhard of the University of St. Thomas in Houston transcribed much of Bermuda’s Slave Registers for 1821 and 1834. They have been made publicly accessible with her support, and the support of the Bermuda Archives team and the first Bermuda Ombudsman. The Bermuda Archives has also developed working spreadsheets for the 1827 and 1830 Bermuda Slave Registers.

The spreadsheets include the number, names, sex, and occupation of enslaved people alongside the names and sex of enslavers. The ages and birth places of enslaved people may be searched in microfilm of the originals at the Bermuda Archives.

Bermuda National Trust is pleased to provide public access to the following spreadsheets of the Bermuda Slave Registers, with permission of the Bermuda Archives in the Ministry of Education, Government of Bermuda.

Bermuda Slave Registers. Photo Credit: Bermuda Archives

Please note:

Bermuda Archives staff and affiliated researchers continue to revise these working transcriptions, including filling gaps and correcting transcription errors.

The spreadsheets reflect the original language transcribed from the original historical documents, except for the column headers which have been edited.

Bermuda Slave Register 1821 (Bermuda Archives Reference: RS 01/01)

Bermuda Slave Register 1827 (Bermuda Archives Reference: RS 01/02)

Bermuda Slave Register 1830 (Bermuda Archives Reference: RS 01/03)

Bermuda Slave Register 1833-34 (Bermuda Archives Reference: RS 01/01)

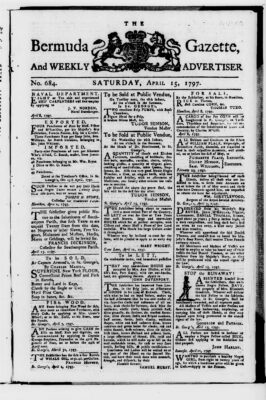

Royal Gazette & Weekly Gazeteer published 15 April 1797

While doing research for her book, Dance Bermuda, Conchita Ming took note of advertisements in the newspaper about the escape or sale of enslaved people in Bermuda. As she read the ‘heartwrenching’ ads, she felt compelled to write them down, until she eventually compiled all such ads published in the Bermuda Gazette (later Royal Gazette) from 1784 until Emancipation in 1834. Conchita says, “I found myself cheering for those who ran away, especially if they were ‘at large’ for long periods. The newspaper did not report if ‘runaways’ were caught so it is not known what happened to them. They are heroes, nonetheless, yearning for freedom. I wanted to ‘Say Their Names’, to acknowledge them and even recognise their skills which helped to ‘build’ Bermuda.”

Conchita Ming has generously shared her compilation of enslaved advertisements with the Bermuda Archives where she conducted her research and they have permitted the Trust to share the compilation here.

Say my Name, Runaway & Sale of Slaves, Bermuda 1700s to Emancipation